| Home | Features | Club Nights | Underwater Pics | Feedback | Non-Celebrity Diver | Events | 18 July 2025 |

| Blog | Archive | Medical FAQs | Competitions | Travel Offers | The Crew | Contact Us | MDC | LDC |

|

|

|

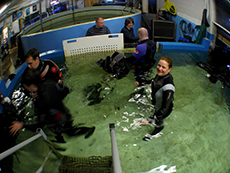

ISSUE 16 ARCHIVE - DEEP SEA WORLDHE SawyerTinkerbell glides over the Perspex tube, seemingly oblivious to the fascination within. Suddenly the spell is broken, her audience distracted.“There’s someone out there. Look!” Cue pointing and nervous laughter. A kid scans the underwater landscape – then waves. Immersed in chilled gloom, surrounded by sedentary sharks, The Girl Who Works in Room 101 waves back. Our story begins on the 4th March 1890, which probably dawned a bit chilly in the Kingdom of Fife. HRH Edward Prince of Wales taps a commemorative gold-plated rivet into the Red Behemoth that is the Forth Rail Bridge. Everyone claps, cheers, and throws their hats in the air. Without a trace of irony, the Prince hands the hammer to a lackey, the hubbub subsides, and the womenfolk start queuing for the privy. The world is changing at an unprecedented rate; civil engineers and bridge designers, Sir Benjamin Baker and Sir John Fowler are seeing to that. They’ve half the alphabet after their names already. Fowler’s engineered the Metropolitan line, the world’s first underground railway, and now Baker’s off to supervise the Aswan dam. They’re leaving behind an icon, and a ginormous hole, mined for the rock needed to cantilever the greatest steampunk bridge ever seen. A century later, some bright spark looked into their abandoned quarry and thought it would be a great place to build an aquarium, fill it with sharks, and stick a car park over the top. So they did. The Edinburgh train trundles across the bridge and deposits me at North Queensferry. The narrow lane tumbles headlong down the hillside, half the panorama dominated by red steel spans, half by picturesque dwellings scattered like dice, pooled at the water’s edge. The Ferrybridge Hotel waits, welcoming, bathed in late afternoon sunlight, with the Deep Sea World aquarium just a minute stroll round the corner. Dive Officer, Tina Aydon, greets me in reception, heralded by the theme from ‘Pirates of the Caribbean’ – they’re running a promotion – kids in costume get in free. Fortunately the marauding hordes have left with their parents for the day, so we’re afforded safe passage through the labyrinth. Originally from Christchurch, New Zealand, Tina conducts outreach trips to schools, taking portable rock pools into the classroom to engage everyone from nursery to university level. There are marine biologists and zoologists on the staff of six full time divers, and the aquarium is a major Scottish tourist attraction. Displays showcase everything from breeding piranha to a rock pool of indigenous coral and anemones, with a vivarium of salamanders and a fistful of tarantulas thrown in for good measure. The centrepiece of Deep Sea World is the 112m long moving walkway that loops through the main tank. Everything looks smaller through the convex glass, although naturally the sharks stand out, Tinkerbell being the mamma, coming in at 3m long. Patch, Hook, Scout, Lewis, Iona and Arran make up The Magnificent Seven. The rest of the tank’s supporting cast are all species native to British waters, including sea bass, cod, pollock, lobsters, crabs, and a reclusive conger eel. Unfortunately I’ve missed the love action. Scout, the newly acquired male sand tiger from an affiliate in Ireland, decided to establish his credentials with the ladies. As I’ll learn on tomorrow’s PADI Shark Awareness course, males don’t take their intended to the pictures, fumbling around on the pretence of looking for the sweets. They bite their way up the torso of their intended to manoeuvre themselves into position for what comes naturally. Unfortunately Scout chose to date Tinkerbell who, ever the diva, bit back, hard enough to leave one of her fangs sticking out just behind his eye. Definitely a case of Carcharias taurus coitus interruptus. “The vet wasn’t too impressed”, Tina adds. Johnny Rotten grins and fins off into the gloaming. And sand tigers are ideally suited for aquarium life because they’re considered ‘low maintenance’. The sharks are fed twice weekly on trevally and saithe, oily mackerel only occasionally. Their food is bought in from local fishmongers. Which leads to the delicate matter of ‘collateral damage’. Tina and her team carry out regular head counts of the stock, but even so there are ‘civilian casualties’. She points out ‘Stumpy’ the gilt-head bream, who flutters round the tank like a wound down clockwork toy, missing his tail. Backstage, we enter quarantine. Here new arrivals spend time under staff supervision to ensure they’re fit and healthy before being introduced front of house. Specimens are donated by the public, such as the small moray eel, whose owner moved house. There’s also an influx from local fishermen who discover curios in their lobster pots. One of the advantages for Deep Sea World is that unlike many aquariums they don’t have to manufacture salt water, as it can be pumped directly from the Forth. Water temperature is kept at a minimum of 12C for the shark’s benefit. Outside on the deck there’s a seal pool, home to a couple from Belgium. Although they can’t be released after long-term captivity, Tina hopes their pups will be, if they can be trained to hunt. Speaking of which, I’m hungry and Tina has a home to go to. I settle in with the menu at the Ferrybridge, and as it’s a Friday there’s a disco. So if you’re staying there, I guarantee you will feel the vibe. They finish around midnight with The Proclaimer’s classic, ”I’m Gonna Be (500 Miles)”. Priceless. There’s a queue before opening time. A band of child pirates keep the divers in check until the five of us are ushered into the classroom for the PADI Shark Awareness course, under the instruction of Chris Rowe. After a brief round of introductions it transpires this experience is a popular gift for the boys from their significant others. Now we know what they’re in hysterics about on a Girl’s Night Out. Not Rose though, she’s not missing out on the opportunity and is going in with partner Graham. Chris takes us through the course, covering shark biology, their cartilage composition, their use of fins, and the idiosyncratic shark skin, coated with denticles to minimise drag. We’ve developed this shark technology for swimsuits, boats and planes to make them more efficient. Naturally the most absorbing section of the course covers shark teeth, continually replaced every eight to ten days, rotating into position on a ‘floating’ jaw which gives the predator extra ‘reach’ for attacks. Something I didn’t know was that the bite pressure of a shark is comparable with our own. Chris encourages us to have a stab at trying to identify and match teeth from various shark species, and although none of us are particularly proficient we all manage to work out which one belongs to a sand tiger. The classroom doubles as a shark mortuary of sorts, with specimen jars containing stillborn Angel shark, and the jaw of a sand tiger, a former occupant. The teeth are needle sharp. Tina warns us that the display jaw, still strangely menacing, has caused more bloodshed than anything in the tank. It exudes an hypnotic suggestion to encourage the curious to see if their heads will pass through. We break to enter the tunnel to watch Tina’s dive team feed the sharks using long handle forks. The divers are all strapping fellows, yet look stunted through the Perspex canopy. Feeding doesn’t take very long and the bucket is soon empty. Tina tells me about a PHD student who carried out research in the tank and observed how the sharks were drawn to their habitual white bucket, which was empty, yet ignored the newly introduced red bucket which contained the food. For us there’s a sit down lunch in the cafeteria which is included in the course fee. The glass wall looks out onto the quarry and the towering red steel above. It’s reminiscent of the Simon & Garfunkel classic, ‘Bridge Over Shark Infested Water’. After lunch we congregate in quarantine to kit up. Dry suits are supplied, but I opt for my own 5mm. Tina hands me twice my normal lead weight. “I want you to sink like a brick.” Fair enough. We split into two, as there are a maximum of four guest divers per group, so Tina and fellow guide Louis Pounder take Dean, Kenny and myself first. We step down into the holding pool where we make our final checks before ducking under the arch and creeping onto the submerged staging in the main tank and the 4.5 million litres of sea water. One by one we descend the shot line to the sandy floor. Once assembled on the bottom we follow Tina’s beautifully articulate hand signals. She makes those telly weather girls look like gimps. There are no fins used in the tank, so movement is unconventional. We walk, single file, leaning forward, like something out of ‘Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea’, keeping a close eye on where we place out feet, mindful of the Angel shark, ambush predators that camouflage themselves on the bottom. Rock habitat funnels us close to the viewing tunnel. It’s amusing to see the faces of those inside following our progress amongst the shoals and sharks. We wave, they wave back, both parties thrilled to be their respective sides of the glass. This is a surreal diving experience. We are most definitely visiting the shark’s home. Situated directly underneath the car park, artificial light paints them silver as they home in from the dark recesses of the rock formations. They’re not going to be skittish and fin down into the blue to 50m, so we are afforded the luxury of close interaction. Crossing the tunnel requires new diving skills. We’ve been briefed to add a couple of short puffs to our buoyancy, then bounce, jump and scull with our hands. Tina naturally makes it look so easy, but the rest of us struggle. I feel mortified with the public looking on, as I imitate a giraffe in roller skates on ice. Louis gives the base of my tank a shove and Tina grabs my flailing hand to pull me over as my finless feet kick thin air. The Perspex is tough, developed by NASA to be used in the windows of the space shuttle. Even so, the aquarium doesn’t want it scratched and dinged by middle aged over-weighted divers. The team spend hours cleaning it to optimise visibility for the viewing public. “There’s a lot of fish poo”, Tina confides. We come upon the Angel shark, buried in the sand. Tina gently uncovers them. She’s convinced the female is pregnant due to her inflated size. We are in the area where the sharks are fed, and scour the sand for the needle-like teeth shed during the feed. Obviously this area brings us into much closer and more frequent contact with the circling sharks. Having been rammed by one some years ago, I’m aware of how much of a punch they pack, even at their cruising speed, and hats off to Tina and her team for capturing Scout to move him to his new home, an operation that involved enveloping the male in a specially constructed stretcher, then manhandling him out of the water. The tank is 6m at the deepest point, although it’s only 3m above the tunnel ceiling. Tina still carries a pony bottle to comply with Health and Safety and there are two members of the dive team stationed on the catwalks above us. They tap on the walkways to notify their colleagues underwater when sharks are moving in, but even now I fully appreciate just how sharp those teeth actually are, at no point during the dive does it feel risky. “The HSE who comes to inspect us is a lovely old boy, and I’ve offered to take him in. But he’s terrified of sharks.” Tina’s developed a shark diving programme for 8 – 15 year olds, evolved from a Bubble Blower course, where the kids view from the railed staging. “I love teaching the kids. They’ve no fear. You tell them what to do, they just do it.” The introduction of kids to sharks was so successful the Spanish parent company released funds for smaller dry suit and boots and hoiked the price, yet even so every junior shark dive is fully subscribed. There’s a feeling within the staff that the parent company should reinvest more in Deep Sea World, seeing as their success subsidises the other European affiliates. Although I still have 170 bar of the 210 I started with, I’m grateful to ascend the shot and emerge from the water after our 45 minute safari. The cold was starting to bite through my wet suit, and I feel a bit guilty for winding Louis up about his need for a hood. We’re quickly brought mugs of hot coffee and tea while we compare “Wow”s and “Amazing”s, and there are hot showers on hand to take off the chill. Mind your step if walking barefoot round quarantine post dive, just in case someone’s dropped their souvenir shark tooth... Once everyone has dry hands, Chris hands round the certificates and the application forms for our ‘Shark Awareness’ certification cards. When the plastic arrives on the doormat a fortnight later it’s a bit of an anticlimax. You would have thought PADI would at least put a photo of a shark on the relevant certification card. Where’s the bragging rights in flashing a scenic picture of a reef when you’ve been in with a sand tiger or seven? If you want that sort of soft coral thing, there’s a Nemo to suit every pocket when you exit through the gift shop. Tina picks me out a cuddly sea horse instead. The rebel. So now it’s just a slog back up that mountain lane to the railway home, lugging my kit, singing through my teeth. You know the words. Altogether now. “But-da I wud wok five hun-dread miles Ann-daa I wud wok five hun-dread more Jus-ta beee tha’ man who wok-ed a thou-sand miles, Ta foll down at yaw daw”. For further information: Deep Sea World Previous article « Editorial Next article » Prawns, an interview with the Environmental Justice Foundation Back to Issue 16 Index |