| Home | Features | Club Nights | Underwater Pics | Feedback | Non-Celebrity Diver | Events | 8 August 2025 |

| Blog | Archive | Medical FAQs | Competitions | Travel Offers | The Crew | Contact Us | MDC | LDC |

|

|

|

|

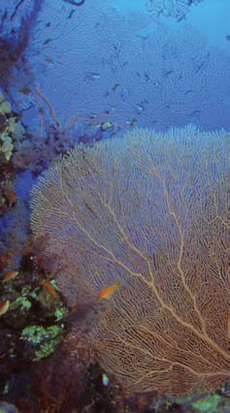

ISSUE 10 ARCHIVE - CORAL REEFS AND THEIR NATURAL AMBASSADORSDr John CarlinThere is something breathtaking about tropical coral reefs. Of course, if you are a captain of a ship then your view could be slightly skewed as they are also a major cause of shipwrecks. For most, though, the warm, clear water, vibrant colours and the vast array of living organisms that inhabit this spectacular ecosystem are a sight to behold. Coral reefs are said to be the most productive, mature, diverse and complex ecosystems in nature.'Coral' is a term generally used for several different groups belonging to the phylum (a taxonomic division) called Cnidaria. Cnidarians are entirely aquatic; a few members are found in fresh water but the majority in marine environments. They have a simple body plan, and are most abundant in shallow, warm-temperature or subtropical waters. |

|

|

Cnidaria comes from the Greek word 'cnidos', which means stinging nettle.

All cnidarians are carnivores, capturing

prey with the tentacles that ring their

mouths. The tentacles, and sometimes

their body surface too (such as

anemones), bear specialised cells

called cnidocytes which occur in no

other group of organisms. Within each

cnidocyte is a small powerful harpoon,

made from a hollow tube with a series

of barbed spines, called a nematocyst.

Nematocysts, fired by water pressure

with enough force to penetrate the shell

of a crab, are used both for defence

and to capture prey. The discharge

of a nematocyst is one of the fastest

cellular processes in nature. They also

deliver a toxic protein, which is why

some cnidarians are referred to as

'stinging nettles'.

The Phylum Cnidaria includes such diverse forms as: jellyfish; hydra; sea anemones and corals. There are four classes in the phylum Cnidaria:

The stony corals (or Scleractinian corals) are closely related to sea anemones, a relationship discernible in their physical appearance, and it is these that build the reefs. The stony corals gain their name from their calcium carbonate skeletons, which allow them to act as the 'bricks' of these massive structures that can extend over wide areas of shallow tropical and subtropical seas. |

|

|

Living coral is a thin veneer, measured

only in millimetres. Yet this thin film of

tissue has created limestone structures

over 1,400 metres thick (e.g. Enewetak

Atoll, Marshall Islands, Central Pacific)

from the surface down to its base on

volcanic rock.

Almost all corals are colonial organisms, composed of hundreds, to hundreds of thousands, of individual animals, called polyps. The colonies of polyps are linked by a common gastrovascular system. Polyps are small fleshy extensions of the coral cover (typically measured in millimetres) compared to the massive size of the colony, which can be metres in diameter. The polyps reside within a cup-like calcium carbonate skeleton, each with a stomach that opens at only one end. This opening, called the mouth, is surrounded by a circle of tentacles that extend into the water column. The polyp uses these tentacles for defence, to capture small animals for food (from small fish down to zooplankton and mostly at night), and to clear away debris. Food enters the stomach through the mouth. After the food is consumed, waste products are expelled through the same opening. As the colony grows, the older polyps die, leaving the calcareous exoskeleton intact beneath as new ones grow on top of them. In this way the reef continues to grow. |

|

|

Coral reefs can be divided into three

main categories: fringing reefs, barrier

reefs and atolls. It should be noted that

many reefs often fall into two different

categories.

Fringing Reefs – These are the simplest and most commonly found of the three categories. They get their name from the narrow bands in which they grow. They are found throughout the tropics and develop near the shore (rocky shorelines provide the best conditions for fringing reefs) wherever there is some kind of hard substrate for the coral larvae to settle on. As they are so close to the shore, fringing reefs can be particularly sensitive to surface run-off (freshwater and sediment) and human disturbance. The longest reef in the world is actually a fringing reef in the Red Sea, which runs for approximately 4,000 kilometres, hugging the coastline. |

|

|

Fringing reefs are made up of a wide

inner reef flat (which is sometimes

exposed at low tides) and an outer reef

slope. The reef flat generally slopes

towards the sea and consists primarily

of sand, mud or coral rubble. The reef

slope has more coral species and live

cover than the reef flat because it is

further away from the effects of

sediment and freshwater run-off. The

reef slope, which can be almost vertical,

also benefits from the good circulation

which brings up nutrients and

zooplankton whilst washing away any

fine sediments.

Barrier Reefs – Barrier reefs can often be difficult to differentiate from fringing reefs as they too lie along coastlines but they are found considerably further from the shore (often 60-100 kilometres). Barrier reefs are separated from the shore (which may have a fringing reef running alongside) by a deep lagoon. These lagoons are usually protected from waves by the barrier reef and therefore usually contain sea grasses and small patches of corals (patch reefs). The barrier reefs consist of a gentle or steep sloping back reef slope, a reef flat and fore reef slope. Again the richest coral growth is usually at the front of the reef (because of better water circulation, nutrients and zooplankton etc.) and although the back reef slope is protected from wave action it is affected by water movement from the waves washing sediment down from the sandy reef flat. The Great Barrier Reef in Australia is considered to be the largest (in terms of area covered) and most famous coral reef in the world. It runs for more than 2,000 kilometres (ranging from 10-35 kilometres wide in places) along the northeast coast of Australia and covers an area of approximately 22,500 square kilometres. It is not actually one reef but consists of a series of about 2,500 smaller reefs, lagoons, channels, islands and sand cays. Atolls – An atoll is a ring reef (and sometimes islands or sand cays) which surround a central lagoon. Atolls are mainly found in the Indo-West Pacific region and range in size from about 1 kilometre to well over 30 kilometres in diameter. As the major reef-building corals can grow only in shallow water, scientists were at a loss to explain how atolls that were found in the middle of oceans, in deep water, could have been formed. In 1842, aboard HMS Beagle, Charles Darwin was studying the atolls of the South Pacific and devised an explanation based on the gradual sinking of an oceanic island over thousands of years. He theorised that fringing reefs can expand over time around the shoreline of an island, and that a lagoon eventually develops as the island slowly begins to sink and the fringing coral becomes a barrier reef. When the island finally sinks beneath the water, the barrier reef becomes a circular atoll. Darwin's theory was backed up when in the 1950s the United States Geological Survey drilled several cores in the Enewetak Atoll in the Marshall Islands. The results revealed, beneath the 1,400 metres of calcium carbonate deposited by the corals, volcanic rock. |

| |

|

Coral reefs carry many different labels

and analogies. Whilst they are called

Pandas of the Ocean (for their

conservation appeal) they are also

sometimes called the 'Canaries' as

they are sensitive to environmental and

anthropogenic changes. Coral reefs have

suffered long-term decline because of a

range of anthropogenic disturbances

and are now also under threat from

climate change. There are no longer

any pristine coral reefs and an

estimated 30% are already severely

damaged, and close to 60% may be

lost by 2030.

The reasons for the decline in reef health are varied, complex, and often difficult to accurately determine. While natural events such as storm damage, predator infestations, and variations in temperature have some impact on reef ecosystems, human activity is a primary agent of degradation. Contributing factors include:

Recreational scuba diving on coral reefs has increased massively in the last twenty years due to various reasons such as: more licensed divers, an increased interest in coral reefs and improvements to travel giving relatively easy access to reefs. Although divers can have a detrimental effect in highly localized areas, scientists estimate that overall diver damage accounts for less than one percent of coral reef damage worldwide. Scientific studies have shown that contacts by divers with the reef occur mostly in the first ten minutes of a dive. This is caused primarily by divers adjusting equipment and becoming familiar with the underwater environment. Most contacts (over 80% in most studies) with the reef are caused by fin kicks causing physical damage and over half of these contacts also raised sediment which can smother corals. The scientists observed that most contacts appeared unintentional and were caused by poor swimming techniques, incorrect weighting and ignorance. |

| |

|

Divers holding onto reefs or resting on

them were the next most problematic

actions followed by loose or dangling

equipment.

Male divers were bigger culprits when it came to coming into contact with the reef than female divers. The more training and experience a diver had also reduced the average number of contacts with a reef. Whilst the old adage 'take only pictures, leave only bubbles' is usually included in a dive briefing, camera users were found to contact the reef more frequently than non-camera users. This usually occurred whilst holding onto or kneeling on the reef to steady themselves to take a picture. Scuba divers and snorkellers are natural ambassadors for the underwater world, since this is our playground and office for professional divers. Because we have an up close and personal relationship with the marine environment we are quite often the first people to notice any adverse changes and sound the alarm. We are a deeply committed and active community and there are a number of activities such as supporting Marine Protected Areas, underwater and beach clean ups. The millions of recreational scuba divers and tens of millions of snorkellers represent a powerful political constituency which can influence environmental policy at local and national government levels. What can you do as a diver to reduce your own personal impact when you go diving? The first is to be female. Only kidding – good buoyancy is very important! You want to make sure that you have current dive skills and if not, attend a refresher or buoyancy course to practice your basic skills. Buoyancy is the key, not only to diving safely, but also to protect the marine environment. Good buoyancy control, correct trimming and weighting will keep you off the bottom and protect your shiny dive equipment as well. If you are diving with new or unfamiliar equipment, practice in a pool first. Not only will you get the chance to check it out for size, fit and performance but you will get the chance to see how it affects your weighting. Get some clips. How many times have you seen divers dragging pressure gauges or alternate air sources across reefs or in sand? Not only does this damage the environment but it can also scratch or clog the equipment up with sediment. By attaching equipment to the body with clips you can also reduce your drag underwater. Listen to the Dive Leader. Studies have shown that diver damage was reduced by Dive Leader intervention – both on the surface and underwater. It is important to listen to a briefing as it will highlight both environmental points of interests and hazards. If it is a reputable company they should remind you of the one metre rule (keep at least one metre away from the reef or bottom) or the one finger rule (if you get too close and cannot scull away use one finger on a bit of rock or dead coral to push yourself away). They will also re-emphasise good buoyancy practice and can even intervene underwater if you get too close. |

| |

|

It is also worth noting that inexperienced

divers after a good dive briefing tend to

stay further away from the reef greatly

reducing any chance of contact. Once

you have a greater degree of buoyancy

control you can start to get closer.

Research carried out also showed that

although impacts can be reduced by

education and the Dive Leader, high

levels of damaged coral will be

unavoidable if large numbers of divers

use a reef. Managers of Marine Parks

have recognised this and have begun

to issue permits to certain areas limiting

the amount of divers. They monitor these

sites and after a period of time or

damage the permits are withdrawn

and new ones are issued for different

locations to allow that area time to

recover.

To be an environmentally friendly scuba diver use environmentally friendly propulsion. Be aware of your fin tips while kicking or hovering. Avoid holding on to the reef – many Marine Protected Areas and National Parks ban the use of gloves for this reason. Many enjoy taking pictures rather than taking game or collecting souvenirs. Particularly with the competitive prices of cameras and underwater housings, more and more new divers are taking pictures underwater. Take time to practice buoyancy with a camera before you dive on a delicate environment. People become very focused on the little display and forget about the environment around them. It is not alright to sit on a table coral to pose for a picture! Also take time to learn about the environment you are diving in. A very wise man called Baba Dioum once said "In the end we will conserve only what we love. We will love only what we understand. We will understand only what we are taught." We are the natural ambassadors for the underwater world and we want to demonstrate role model behaviour in diving and non-diving interactions with the environment so that the beauty of the underwater world is there for us and future generations to enjoy. |

| |

Previous article « Manado Next article » An Armchair Diver's Guide to Tech Kit Back to Issue 10 Index | ||